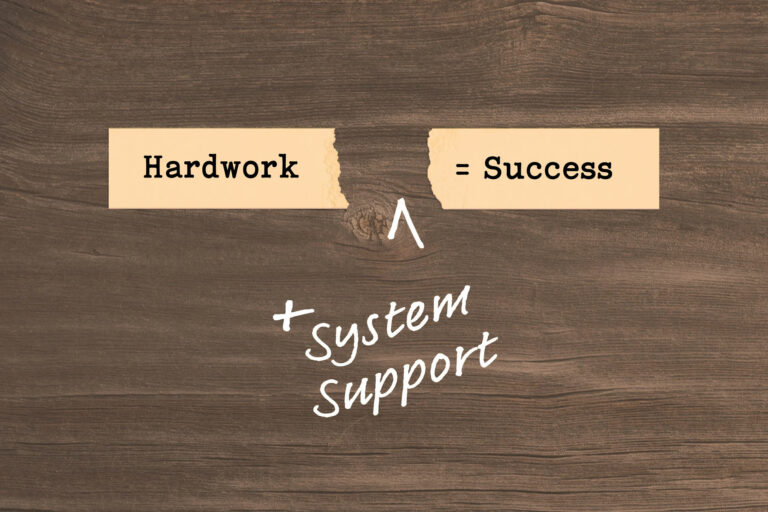

If you grew up in the United States, at some point someone probably convinced you that if you work hard, success will follow, either in the form of good grades, fame, or fortune. And this equation, hard work = success, has probably informed many of your life’s decisions, like when to stick with a difficult task or job and what to say to friends and family when they struggle to accomplish their goals.

But what if this equation is untrue? Or more accurately, what if it’s only half true?

Social scientists have found that the most pernicious barrier to DEI is the myth of the self-made man, also known as rugged individualism. This myth is so implicit and widespread in US society that our minds automatically attribute disparate outcomes between groups to individual effort. So, if we state that African Americans are more likely to be diagnosed with diabetes than White Americans, the average American brain attributes that difference to either better individual effort by White Americans to eat healthfully or less effort by African Americans to eat healthfully. We don’t see the food deserts, housing, and environmental factors contributing to these disparate outcomes. We simply can’t see how systems support some people’s success but not others’ because we have bought so completely into the myth that we all go it alone.

This idea shapes how we tell stories. The Hero’s Journey, a monomyth made famous by cultural and religious scholar Joseph Campbell, is the template used to shape narratives in media, from books and movies to journalism and documentaries. It involves a protagonist who goes on an adventure, experiences a crisis, overcomes it, and then returns home transformed. Everyone from Pixar cartoonists to nonprofit fundraising professionals has been influenced by this template – including public media.

The Hero’s Journey certainly holds people’s attention. But it also makes the system invisible and silent, thereby reinforcing oppressive behaviors and protecting those in power.

If we want to create a more equitable world, we need storytellers to break the silence and become transparent about the system, the privilege it affords some but not others, and the support any protagonist receives from others in their journey to success.

But what about luck, you say? People with dominant identities sometimes attribute their success to luck, I suspect in an effort to be humble. I’ve observed this most often in White men who identify as politically progressive. But let me be clear: crediting luck— no matter how humble your intentions—does not help. In fact, it reinforces oppression because it obscures the system, making it impossible for people with marginalized identities to understand its rules and design their lives for success within it.

The more accurate formula for success is this:

Hard work + system support = success

When we understand this, we realize that someone may not be experiencing success because there is no system supporting them, not because they are not working hard. And consequently, we avoid the logical fallacy of believing that people not experiencing success are simply lazy or unwilling to work hard.

If your station is committed to holding power accountable, then it must begin to tell stories differently, whether those stories are in editorial, fundraising, or even just internal narratives of how Peabodys and Emmys were won. Every story of triumph must highlight the role the system played in supporting that success.

What does this look like?

A few years ago, someone at a client organization complimented me on the success of my company, Brevity & Wit, which grew exponentially between 2019 and 2020.

“It must be hard to start a business. And impressive that you’ve been able to make it so successful,” she said.

“Yeah,” I replied. “But it wouldn’t have happened if I hadn’t gotten married.”

She looked surprised, no doubt because she knows I’m a fiery feminist and that my husband has little to do with my work. But I pressed on.

“I tried to go out on my own multiple times when I was single,” I explained. “But I couldn’t make it work between paying for health insurance and earning enough to live on. Getting on my husband’s health insurance and having his income as a buffer made it possible. It wasn’t a huge buffer—I had to turn a profit within a few months— but it was enough and more than I ever had when I was single.”

The client, a single mother, looked relieved and seemed to appreciate my candor. It was clear I was not going to perpetuate the myth of the “alley cat” entrepreneur who scrapes by no matter the circumstances, while “house cats” take safe jobs with benefits. By talking about the external support I’ve received, I demystified my success and, hopefully, helped my client see the system more clearly. And when more people see the system accurately, more people will be able to intervene to make it more fair and just for all of us.

Speaking a story through a systems lens is not about personally maligning anyone. Moreover, telling the whole truth about your story allows you to responsibly deal with your privilege, whether that privilege is derived by race, sexuality, gender, or any other dominant identity. Too often, people get stuck in feelings of shame or guilt when talking about their privilege, but these feelings are often self-serving. Telling a more holistic, systems-based story of one’s success is more helpful and productive than guilt because it unmasks the system for those of us on the outside who have no idea why we’re working twice as hard to get half as far.

If you find yourself feeling guilty and unsure what to do to help design a more equitable world, then I invite you to explore your personal narrative of how you ended up with the job, recognition, money, or prestige that you have. What system supports helped you along the way? What would your story look like if you were a different race or gender? How would the system support or marginalize you then?

Engaging in this sort of critical reflection of your own story will help you develop system sight, and you can then bring that lens to all your work as a public media professional. This is not just critical for “content folks.” One public media professional shared with me how the idea of system sight helped their organization get out of the guilt and finger-pointing of their own history of organizational decisions. By focusing on telling the story of the system, they were able to own how decisions had been made that led to inequity. And as Brené Brown says, when you own your story, you can (re)write the ending.

Telling stories through a systems lens is the best way to help others develop system sight. And shouldn’t that be the ultimate aim of the media – to reflect the world as it really is? With system sight, people can finally take actions that are informed by reality, not mythology. And that will make for better decisions all around.

Parts of this post were previously published in Equity: How to Design Organizations Where Everyone Thrives (Berrett-Koehler, 2021, www.theequitybook.com) by Minal Bopaiah. You can contact Minal at www.brevityandwit.com to learn about workshops to help you or your team develop an equity lens in storytelling.

Image design: Vidya Desai/Brevity & Wit