We are experiencing a reawakening in America: A global pandemic and failure of our democratic systems. Nearly a decade of watching Black Americans murdered from multiple video angles. The Karens. Mask polarization. The psyche of America is crying out: When will it end? Enough is enough.

The overwhelming feeling is that few solutions – or even substantive conversation – have come from those in power.

It’s no different in public media.

My heart aches when I see/read/hear so many of my media colleagues and particularly those in public media, who have expressed during these past few weeks their lived experiences inside of newsrooms and organizations as being made to feel less than or even invisible.

Those words come from a tweet that I posted back in mid-July. But it’s a statement I’ve been making for the better part of the last decade. These are years when my BIPOC colleagues have been speaking up about their experiences working in public media. Applying for c-suite roles and never being interviewed, being passed over while whites with less experience and questionable pasts get promoted, discovering that white colleagues in similar roles make significantly more, and enduring retaliation for speaking up or filing complaints with leadership or HR.

While some diversity might exist at the bottom of our organizations, as you summit the peak of leadership, it’s snow-capped white. It’s the public media version of a 1960’s lunch counter. It’s modern day segregation.

Just as our nation has grown angry over failed systems we thought were meant to keep us safe, healthy, and employed, BIPOC folk have grown angry at the years – decades, centuries – of systems that fail us. But in a white-dominant culture that views our anger as “dangerous,” even violent, we’re asked to subvert that facet of our basic humanity: emotion.

I too have had my own #PublicMediaStories. On several occasions I have felt as being ‘other.’ On several occasions I’ve been asked to speak on behalf of people of color. On several occasions I’ve had to defend why my passion as the only brown person in the room was being misconstrued as anger. On several occasions I’ve had to take on the Google role of historian on race. But I wasn’t asked how I’ve been able to raise millions of dollars in underwriting and sponsorship, how I was able to win three Emmy Awards, how I launched two podcasts within months of each other, why so many people call me to be their mentor and advisor, and how I’ve been able to build a strong and powerful coalition of the willing along the way.

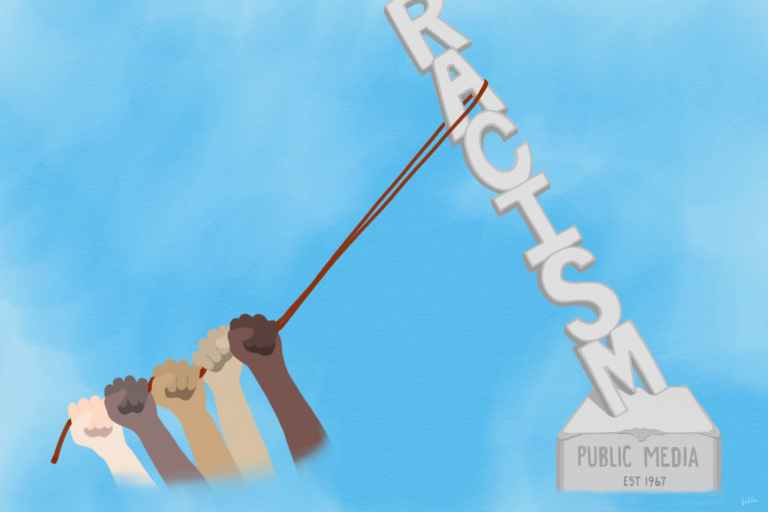

It’s no surprise that public media statues have begun to fall in a reckoning unlike anything we’ve seen. Public media’s internal whiteness, and some even say white supremacy, has fueled a tsunami of grievances that public media leaders have been complicit in ignoring, hoping that it’ll go away.

Instead, this moment is happening because of a broad coalition of public media staff who are refusing to stay silent.

Our organizations include growing numbers of Gen-Xers, Millennials, and Gen Z. These are individuals who were raised to embrace the values of transparency and accountability. And, in the face of injustice, these are what they, in turn, demand from their organizations. I’ve personally coined these three combined generations, the Now Generation. They live in a world of on-demand, instant response, and little pretense. Other generations have grouped them as well, calling them entitled, lazy, and self-centered. I disagree, and I know my response will be viewed as generationalist. But what other generations must understand about the Now Generation is that their response to injustice will come with the immense scale and reach of social media. They bring a network of action.

The Now Generation has brought their grievances to HR departments and leadership systems that are relics of the past. These systems silence complaints with threats of hierarchy, dangling carrots, NDAs, or, even worse, job loss.

What we fail to see is that the Now Generation has endured the worst economic crisis in modern times, twice over if you include the pandemic. They saw their parents lose their jobs, their homes, their retirements, the so-called American dream. So, what has the status quo delivered for them? Nothing. They will protest publicly; and question (rightfully so) the construct of objectivity in journalism. Ultimately, they will speak truth to power, be it to the government, society, or their boss.

We now have public media employees unafraid of expressing their work experiences on social media. Such posts demonstrate an incredible amount of courage and bravery to speak publicly about lived experiences with racism. These social media posts, and countless others that remain private in closed social groups, are a direct result of tone deaf, out-of-touch, outdated leadership.

What leadership has failed to understand is that American society and our organizations are racist. In order to move into the future, our organizations must reckon with the past by becoming anti-racist. What is the actual demonstrable evidence that one is anti-racist? This is what the Now Generation will demand, unrelentingly.

Public media leadership, boards, and staff, must reflect the communities they serve, not just current audiences or donors. This was built into the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967. But before we can address unserved and underserved communities as the Act suggests, we must de-marginalize the voices within our organizations. Until we do so, we are ill-equipped to handle this crisis. Representation and change must come from within.

We must radically reimagine the future of public media, now.

We must become more transparent in how senior leaders are vetted and ultimately chosen for leadership roles. Leaders should publicly campaign for their promotions by putting forth vision plans and allowing staff, and the community they serve to question those plans, and cast their vote with equal decision-making weight of a board.

Public media leaders must be accountable for the outcomes of their stations, which includes culture. A toxic culture is the result of toxic leadership. Growth and bottom-line success should not come at the expense of egregious behavior. We must tear down the facade of public media success that’s defined by an annual report and establish new performance benchmarks that look at the triple bottom line: people, planet, profit.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, we must fully examine the role that BIPOC talent plays in furthering public media’s mission. The anemia of diversity within public media should be viewed as a deficiency of leadership. We can no longer build out three-to-five-year talent plans that take a staged approach to diversity across content, audience, and revenue. It needs to happen now. The current power structure has endless excuses about why they can’t do certain things. As I say to my seven-year-old, in the amount of time it takes to argue about something, you could have actually done something. Talk less. Do more. And this time when we come at segregation, let’s start at the top, not the bottom.

Implementing these changes is a moral and ethical necessity. It’s core to our mission as a public service. It’s also a critical business imperative. Anything less, is a complete failure in meeting this moment.

And one more thing.

Public media isn’t my only option. I say this not as a threat. I’m saying this as a signal to myself and others looking to the night sky. Having run several multimillion dollar businesses, having worked in corporate America, having gone to public school, and having been the first in my family to graduate from college, I know my worth. I know what our communities are worth, I know what my colleagues are worth, because of the value they bring to these highly venerable institutions called “public” media that don’t reflect the actual public… yet.

There’s one kind of insurance that you cannot buy but yet it’s most plentiful, widely available, and as necessary as oxygen. It’s me and my diverse colleagues. It’s up to you to decide if we have a seat at the table. Whether you’re a board member, university licensee, or public media leader, you should be measured not by whom you exclude, but by whom you include and how they succeed. Those words come from the charter of my own licensee, ASU. In our most vulnerable moments, the human mind turns to scarcity, but I find myself seeing abundance, because my life’s experience has always been about doing more with less. This is a moment and opportunity like no other. Will we seize upon it or return to the ways of the past?

This is about leadership for the Now Generation, not next.

This essay is part of Greater Public’s thought leadership series focusing on whiteness in public media. This series embraces bold, honest thinking that points the way toward public media’s brightest future.