Related Articles

Subscribe to the Greater Public newsletter to stay updated.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

We recognize that many in our industry are facing immense stress and fatigue right now. This essay discusses serious themes of depression and suicidal thoughts through the lens of music and personal experience. If this topic is difficult for you, please read with care. Remember you are not alone: help is available 24/7 by calling or texting the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline in the U.S. and Canada.

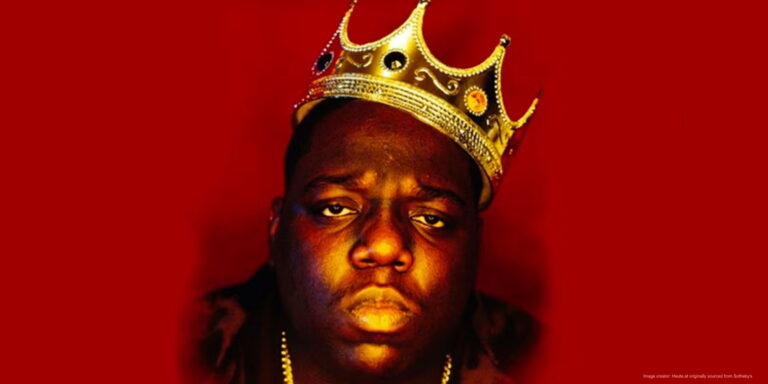

We owe Biggie an apology.

When Ready to Die, the debut album from the Notorious B.I.G., dropped in September 1994, it was three weeks after my 11th birthday. Like most hip-hop kids, I memorized every hook, danced to the R&B-infused beats—and missed the glaring truth: Christopher Wallace was describing profound depression.

Biggie was only 23, yet he named his first album Ready to Die and—almost prophetically—his follow-up, Life After Death. The closer of that debut, “Suicidal Thoughts,” ends with the sound of a gunshot and a dead phone line. We rapped along as if it were just another banger.

I didn’t understand what I was absorbing until adulthood, when conversations about depression and suicide became real in my own life.

And as someone who now works in and around storytelling—through hip-hop, writing, and public media—I’ve come to see that sharing our truths, whether through a verse or a broadcast, can be a lifeline. Both art forms exist to connect people who might otherwise suffer in silence.

The conversation around mental health is ongoing, and as the 30th anniversary of Ready to Die reminds us, hip-hop has been confronting these struggles far longer than the world has been willing to listen. As a Southern Black man raised in a family that mistrusted therapy—and barely acknowledged the “F-word,” i.e. feelings—I now hear Ready to Die as a desperate cry for help that we, as fans and as a culture, largely ignored.

Back then, many dismissed critics of hip hop lyrics like C. Delores Tucker, a civil-rights veteran who marched with Dr. King, as out of touch. I understand now that she sensed something deeper than profanity and bravado. Behind the B-words, N-words and hardcore beats lay immense pain—a truth that shaped me as a writer, activist and hip-hop artist.

Hip-hop has always held that pain in plain sight. In my hometown, clubs host annual March 9 parties—marking the day Biggie was killed—yet few fans can name his birthday (May 21, for the record). I’ve stood in those rooms watching people dance on the anniversary of his death, feeling uneasy. It’s the same dissonance as dancing to Crystal Waters’s “Gypsy Woman,” a house classic about homelessness whose chorus—la da dee la da da—we belt out while this woman suffers.

We’ve done the same with other icons. Tupac envisioned his own death in videos like “I Ain’t Mad at Cha.” Scarface has rapped vividly about suicide since “Mind Playing Tricks on Me.” Beneath the braggadocio and clever rhyme schemes was a generation of young Black men processing trauma the only way they knew—through music.

Today’s artists are carrying that conversation forward. Kid Cudi has become one of hip-hop’s most visible advocates, speaking openly about depression, suicidal thoughts and the rehab stint where he suffered a stroke. Kendrick Lamar’s Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers plays like a recorded therapy session, exposing family conflicts, sexual trauma and raw self-examination.

These acts of public vulnerability are vital when the suicide rate among young Black men is climbing. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, suicide is the second-leading cause of death for African Americans between the ages of 15 and 24. As Michael Curtis, co-author of a University of Georgia study published in Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, explains: “We found when Black men were exposed to childhood adversity, they may develop an internal understanding of the world as somewhere they are devalued, where they could not trust others, and they could not engage the community in a supportive way.”

In many ways, that’s the mission of public media, too: to make people feel seen and less alone. When we talk honestly about mental health in our communities—through music, conversation, or storytelling—we create the same kind of lifeline that once came through a verse, a radio dial, or a familiar voice saying, “You’re not the only one.”

That acknowledgment is why people keep listening or become members. Not because they owe public media money, but because public media has already given them something — a voice, a story, a moment when they felt understood.

People didn’t listen to Biggie because he was polished — they listened because he was real. That’s the lesson for public media as it tries to stay relevant: relatability over credentials, connection over perfection. Public Media doesn’t have to have all of the answers, but holding a mirror to the world to help the people make their own decisions is just as vital if not more.

Hip-hop, including the world Biggie came from, still carries an unspoken wall of cultural silence—one that hasn’t broken down as much as we might hope.

When it comes to Black men struggling to talk about depression or suicide, the silence isn’t new. My family is from rural South Carolina, and I grew up hearing my father’s stories of picking cotton as a child. Both of my parents attended segregated high schools and held the same jobs for more than 40 years. But in all those years, no one ever asked—or perhaps even wondered—how my father felt about anything.

I once staged a one-man show in my city called “Black AF.” (My mother thought it stood for “Air Force” until she arrived.) Part TED Talk, part performance, part confession, it was the first time I publicly described my own brush with suicidal thoughts and an attempt. I stood onstage, tears running, telling the audience—including my mother—that I wanted to live, and that therapy had given me tools to cope.

Afterward, I told my mom I wished my father had been there. She said she was relieved he hadn’t, because in her view he would have lost respect for me for admitting to those thoughts.

It’s been 30 years since the release of Ready to Die, and my relationship with dancing to inappropriate things in hip-hop remains paradoxical. We all jumped to Kendrick Lamar’s “Not Like Us” during that unforgettable “A-minor!” hook—maybe a different kind of trauma, but proof that joy and pain often share the same beat.

Whatever darkness I faced as a young hip-hop fan, something always pulled me back from the edge. I hope today’s listeners find that same lifeline—and that, now in “unc” status, I can offer what my generation rarely did: perspective and empathy for the struggles hidden in the music.

Maybe that’s the yin and yang of Biggie’s spirit. Despite an album titled Life After Death, we remember him most for the breakout single “Juicy,” where he declares, “Damn right, I like the life I live, ’cause I went from negative to positive / and it’s all… it’s all good.”

That much I know.

View these related member resources and more with a Greater Public membership:

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

New to Greater Public? Create an account.